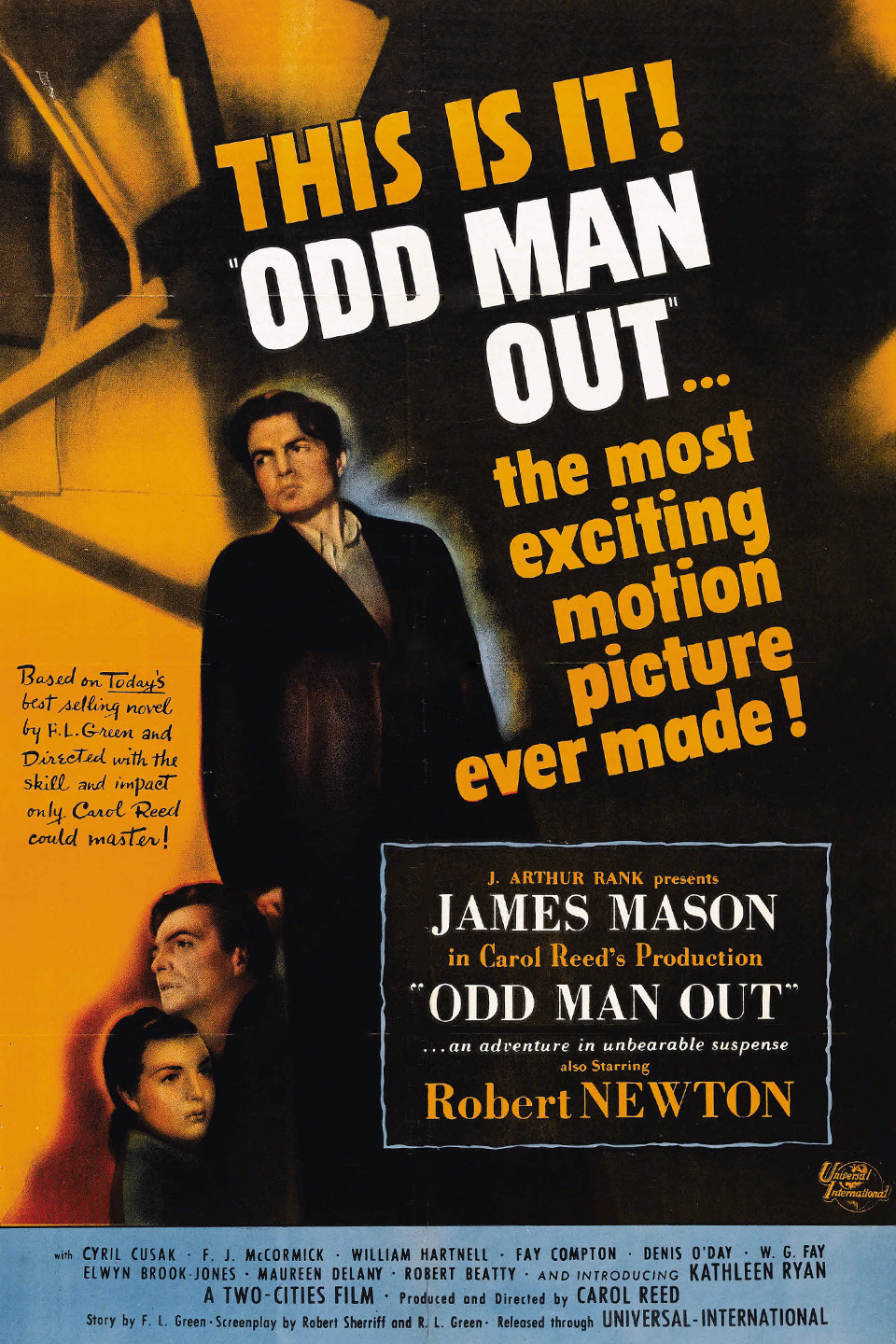

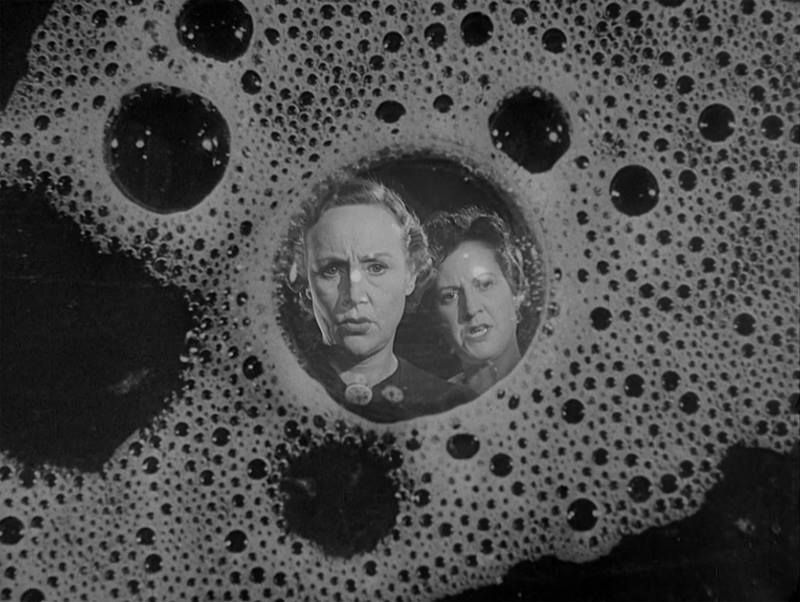

A powerful film. The camera and acting direction is very well choreographed in this movie such that they both work with each other to tell the story as best as possible. The camera tells the story in a way that both directs and follows the natural action of the scenario. When it moves, it moves to reveal elements of a chase scene, or someone overhearing something, or someone coming down the hall in a way that times exactly with the actors blocking and emotional performance so that you experience suspense and subjective suspense at that. I said earlier that we had entered into a period now, during WW2, where the camerawork becomes more subjective in the notion that shots or effects are designed to affect the audience to enter a similar state of consciousness and psychology as the character. This is most notable in this film during the highly famous (noted in the story of film movie) “troubles reflected in bubbles moment” when James Mason knocks over a bottle and the liquid pours out and the camera zooms into the bubbles to show him the recap of what had happened to him. This sequence is noted for being copied by Scorcese in Taxi driver and other directors who knew of Carol Reed’s work.

In addition to the camera movement the film employs double exposures and blurred sequences to enhance this subjective experience of being in the crazed mindset of James Mason. The editing as well works towards this effect, notably at the beginning during the initial bank robbery sequence we see James Mason unable to move and the camerawork reflects that paralysis as well as towards the end when he is losing blood and sitting in the chair to be painted and watches the room transform in front of him. Even the moment when he sees a “policeman” walk into the bunker and it is in fact a little girl the editing and camerawork is tricking us as the audience to believe the same things he sees, to put us in his mental state.

This movie sets precedents for several after it. I can’t think of anything before this film that does the “heist” sequence as well as this movie does. The bank robbery sequence and getaway and subsequent scenario of a guy on the lamb has never been done like this before, in regards to the editing, the timing, and the suspense it elicits. This method for shooting and editing even writing a heist sequence is the template for all the heist and bank robbery movies that follow throughout time, notably Heat.

Again, this is the era of WW2/post WW2 where the anti-hero sets in and the protagonist is also the villain. The monster moved from external circumstances to inside the house/family, to now inside the person. As this man grapple’s with his own wrongdoing we realize he is the monster. That’s a new one:

THE PROTAGONIST REGRETS HIS DECISIONS AS THE VILLAIN AND ACTIVELY FIGHTS AGAINST HIMSELF.

Whereas before, the protagonist who was also the villain would usually fight for his own survival and not against himself. That is a new conflict, protagonist vs. himself.

This is an underrated movie. It poses serious philosophical dilemmas pushing film once again to the status of very high art as opposed to just escapist entertainment.